Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop

by Hwang Bo-reum

translated by Shanna Tan

Before I started sweeping floors and washing dishes at Silvercup Studios, before I started firewatching c-stands at 42nd and Lex or herding talent at Macy’s overnights in Jersey City, before I went off on a snipe hunt for a box of f-stops [apocryphal]—before, even, I started working with chatbots and ARGs–I labored in the academic mines of Columbia University’s Telecommunications Department.

While most of what I did during my apprenticeship in B-school centered around textbook editing and Africa as an emerging wireless market, the broad concepts within the incipient rise of Korean telcos–this was the era of Gagnam Style (강남스타일)–really informed my view of the country. I knew very little about Korean culture beforehand; Columbia was blessed with proximity to The Mill, a popular dining spot for the university crowd, and without this conflux of research and lunch I would have had little and less experience with anything Korean.

In retrospect, my exposure tracked pretty well with the standard American cultural understanding of Korean stuff. 2011 was the anterior cusp for what is now the almost ubiquitous success of the K-drama, the Netfix-sourced Korean gameshow, the global reach of K-pop. Books have followed in the wake of visual and aural media—a modest parade of international bestsellers [Tteokbokki] and Korea-focused memoirs and novels [H-mart, Your Face] that have ridden the ascendance of Korean digital media saturation. All of the image-based content with which American markets have been inundated has its origin in foreign national telecom politics and, dare I say, foresight.

In short, Korean pop media culture came of age with images already embedded. Comparatively, when one thinks about American music it’s colloquially about Billboard Top 40 Hits–radio hits, even if the American population rarely listens to terrestrial radio signals anymore. Music videos were an appendage–MTV was an upstart, not a core tenet–of what it meant to be a popular musician in America.

Korea’s national music scene expanded through the promulgation of video. Choreography and image was inherent to the heart of k-pop.

As I continue to consume the increasing quantity of Korean media available through Netflix, I feel assured that my increase in interest about Korea is not simply informed by my location–San Francisco is relatively supportive toward members of east Asian diaspora communities compared to much of the rest of the US–but by larger factors that I recognize due to past academic research into globalized popular telecommunications trends. The market penetration of Korea’s visual media output–again, founded in real political and technical decisions that are historically traceable–makes it ripe for continued promulgation in American consumption. Put another way: Americans, we like to watch our entertainment on a screen.

But I like books. So I like that there are Korean bestsellers being translated and marketed to me, and I don’t think I would necessarily be seeing them at bookstores without the success of other Korean media. American markets like Korean stuff. Thus more stuff will be available. As one of the characters in Hyunam-dong Bookshop asserts, “Once a movie crosses the three-million mark, the production company will use it to further promote the movie and that’s how it will sell the four millionth ticket.” Popularity is breeds popularity. It is how it goes.

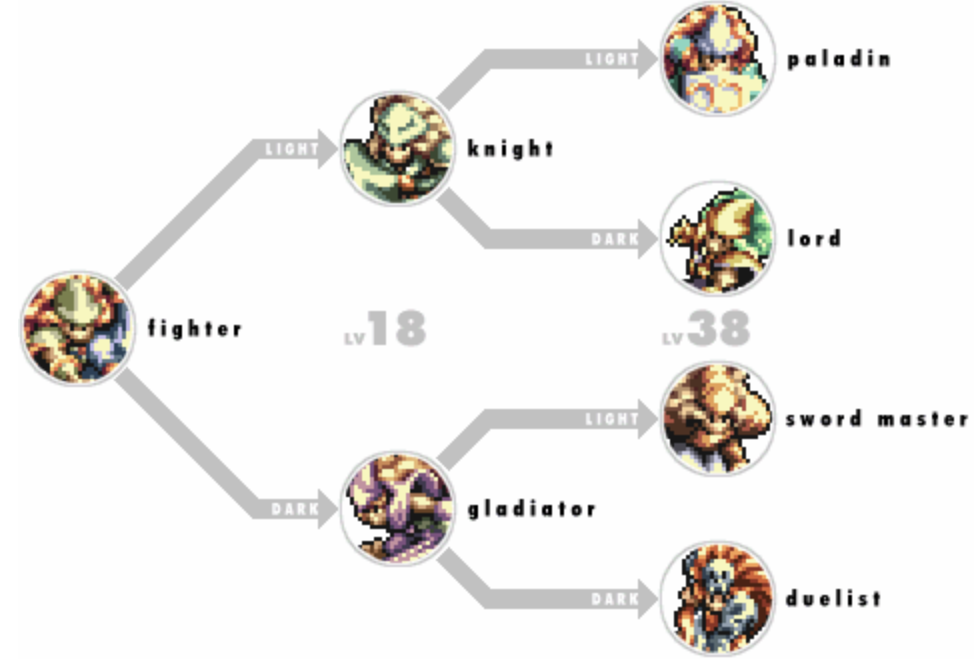

I think I did Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop a disservice by simply assuming it was going to be a Korean version of Days at the Moriksaki Bookshop. It’s not even close. It’s barely even the same genre. Functionally, Hyunam-dong has a lot more in common with a traditional role-playing game: you follow Yeongju, who has her quest of running a bookshop; she recruits a ragtag band of uniquely talented adventurers to help her achieve her goal:

The four of them shared a table. Seungwoo and Mincheol were there first, seated across from each other. A while later, Jungsuh joined them and soon after, Minjun sat down with a cup of coffee. While Seungwoo was editing, Jungsuh was crocheting and giving Minjun feedback on his coffee as he listened attentively. Mincheol, as usual, was staring at Jungsuh’s hands, occasionally throwing questions at the three of them in turn.

…Meanwhile, seated behind the counter, Sangsu was leisurely leafing through his newest read in between attending to customers, while over at the bookshelves, Yeongju was checking the sales records and deciding where to shelve the books she’d ordered that day.

The author herself notes that she didn’t really have an overarching plot, she had the idea of the characters and the setting of the bookshop, and then kind of ran them into each other to see what happened. “Whenever a new character stepped in, I gave them a name and fleshed out their personality. If I had no idea what came next, I’d get the new character to chat with the older ones, and somehow, they seemed to guide the story and the next scene would come naturally to me.” This sort of generative storytelling is what gives Hyunam-dong its “real-play” tabletop RPG quality [i.e. Dungeons & Dragons], and for a novel whose main storytelling conceit seems to be characters struggling with what it means to work, almost all of the growth comes from accepting a role outside of the standard system of employment.

Few moments mean much beyond the transcription of events as they happen; there is little metaphor or symbolic interpretation at work within the pages. Character growth seems linear–again, like an RPG–where each character in the story has an issue that they confront and then resolve: being a part-time employee makes Jungsuh sad, but meditation helps her accept it; Yeongju want to run a bookshop but it is potentially unsustainable, yet she learns to accept the risk one day at a time; Mincheol feels like life has no broader meaning, but eventually finds meaning enough in simply existing. Characters grow into themselves in the same way a squire grows into a knight–none of them truly change, they just sort of prestige into the next tier of themselves.

I think a lot of people, me included, enjoy the planning and preparation phases of RPG gaming–choosing the character’s individual skills or the synergies inherent in team compositions is often more fun than the actual encounter resolution. I think an RPG set in a business (that wasn’t like Recettear or Moonlighter, where you have a traditional dungeon crawl to get items to sell in your shop) would be really interesting—more a blue sky Cart LIfe, where your skills are about making a better cup of coffee, or having more eclectic tastes to better distinguish your shop from rivals, rather than unlocking more fanciful sword flourishes.

But crafting out a “build” in real life doesn’t work–if I had followed the linear growth of a traditional career, I wouldn’t have turned up at Columbia, which would have precluded much of my foundational opinions on Korean media output. So seeing the characters move in such a straight line is what makes Hyunam-dong feel like you’re reading a stage-play, but one without any larger insight into the human condition. That’s not to say it’s bad–they characters are pleasant—but I briefly referenced a bunch of work I’ve done in the past at the start of this article to inform readers that a straight line of employment through life is no longer very common—and without a purpose, metaphorical or allegorical or otherwise—it comes across as less textured than reality. The book is oddly flat: to put it in RPG terms, there is simply not a lot going on with the actual gameplay mechanics. The people in the bookshop do, indeed, just sort of bump against each other, bumble their way into a self-actualized resolution of their singular issue, and then exposit opinions on how life works that I interpret as mirroring the author’s own mind:

There is a reason that real-play TTRPGs are popular storytelling, though—the bumping of broad personality types into each other can create some interesting moments:

First, she would quit her job. When she informed [her husband] Chang-in of her decision a few days later, he was surprised, but he accepted it. However, it wasn’t enough for her. She wanted him to leave his job, too. If his life continued on the same trajectory, she felt as if she would be living with her past self; whenever she looked at him, it was if she could feel her throat constricting, and her heart squeezed as the tears flowed. He should quit, for her sake. He shot down her request, of course. For several months, they clashed over their difference of opinion, until one day, she suggested that they end their relationship.

The “of course” up there is the difference between Yeongju being likable and not–the unreasonability of her desire is the first time her character has what I would call an interesting flaw, but the narrator recognizing it was unreasonable even as Yeongju stuck to it was powerful work. But no one else in the book really has that depth—their backstories don’t intrude upon their journeys, and so the conclusion to each personal quest for the other characters seems an inevitable outcome impelled by outside forces rather than a consequence of events we as readers get to participate in by virtue of seeing.

By the end of the book, I felt like I got to know one person really well–the author. I think her opinions on finding joy in the balance of work and life and taking risks (if there is any sort of metaphor here, it is that one could swap in “opening a bookshop” for “writing a fiction novel”) all come through, but it does make each character in Hyunam-dong feel like a piece of the author’s psyche rather than a full person. If I was being more charitable, I would call the whole thing a story of personal revelation, but I’m not. It felt like grounded fiction with characters that didn’t exhibit a whole lot beyond their solitary trait.

It’s a pleasing read, but, as Yeongju recognizes when she stops carrying bestsellers in the Hyunam-dong bookshop, bestsellers often get there for reasons beyond their control. “A book becomes a bestseller because it’s a bestseller.” The same can be said for national media—Korean programming has become popular in America, so more Korean works become available, in an ever-increasing spiral. So, “…she would seek out books with similar themes and stock them instead. Customers who came in looking for the title would be directed to these books.” I wouldn’t go as far as to not stock Hyunam-dong, but one must ask; are there books out there with similar themes to Hyunam-dong that the coterie at Hyunam-dong would actually recommend?