Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

by Immanuel Kant

If you’re looking for quick summation of Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, it is, “In conclusion, we cannot know.” If doing a “good” act benefits the doer in any way, then it becomes impossible to isolate motivation: perhaps something “good” was done for a bad reason. Basically, something you choose to do has to 1) screw you personally, and you need to 2) know it’s going to be bad for you, and 3) you choose to do it anyway for it to be confirmed as a moral act. Except, wait, you might be getting some sort of side-benefit from looking altruistic and selfless, so maybe you’re not doing a good act for itself after all but simply to farm aura. It remains quite impossible to know why one does anything, and answering the “why” is what proves out a good person, not observing the action itself. There, that’s the groundwork.

Okay, goodbye first year undergraduates who want to be safe from being cold-called in lecture but don’t want to read an AI summary. Hello, remaining people braced for a lengthy videogame digression. Here’s the thing: when a game designer of, say, a CRPG gives a consequence to an in-game choice, you the player are often weighing material gameplay benefits against 1) the story: would my character do this, either within the script as presented or as the entity I have imagined them to be, and 2) your general play experience: is this action fun for me to do, or tedious? Someone has to create meaning for every decision in a game, from whether or not lying to an NPC will change your character’s reputation to how that reputation is promulgated to other NPCs. Maybe theft is simply a static check against a chance of failure, with “no” moral judgment. If stealing the items in a chest will turn guards hostile or break questchains by making townspeople not talk to you, then the odds of a player simply reloading until they get the outcome they want is high. Pass/fail binaries that make living with consequences not very fun are often eliminated, mitigated, or simply don’t allow the type of theft that, say, gives you key items early. Often the victims of your material larceny don’t even notice it. Immersive Simulation (IMSIM) first person RPGs often color-code items as white for takeable and red (maybe with a little hand) for stealable. The distinction comes down to not being able to sell stolen items unless you find a character flagged as a “fence” or a thieves guild merchant, and perhaps the item being removed from your inventory if you’re caught by guards while doing other crimes. Some games acknowledge rampant theft, but usually just as a joke about how silly these abstractions can be: “Hey, Protagonist, don’t steal my herbs!” Games in the Ultima series are the only ones that leap to mind as trying to actually address avatar moral goodness. One-off events, like the time the gameboy Zelda game shamed Link for opening chests, or the courtroom scene in Chrono Trigger that judges the “moral character” of Crono for committing a bunch of standard RPG actions, simply lampshade standard lack of game morality.

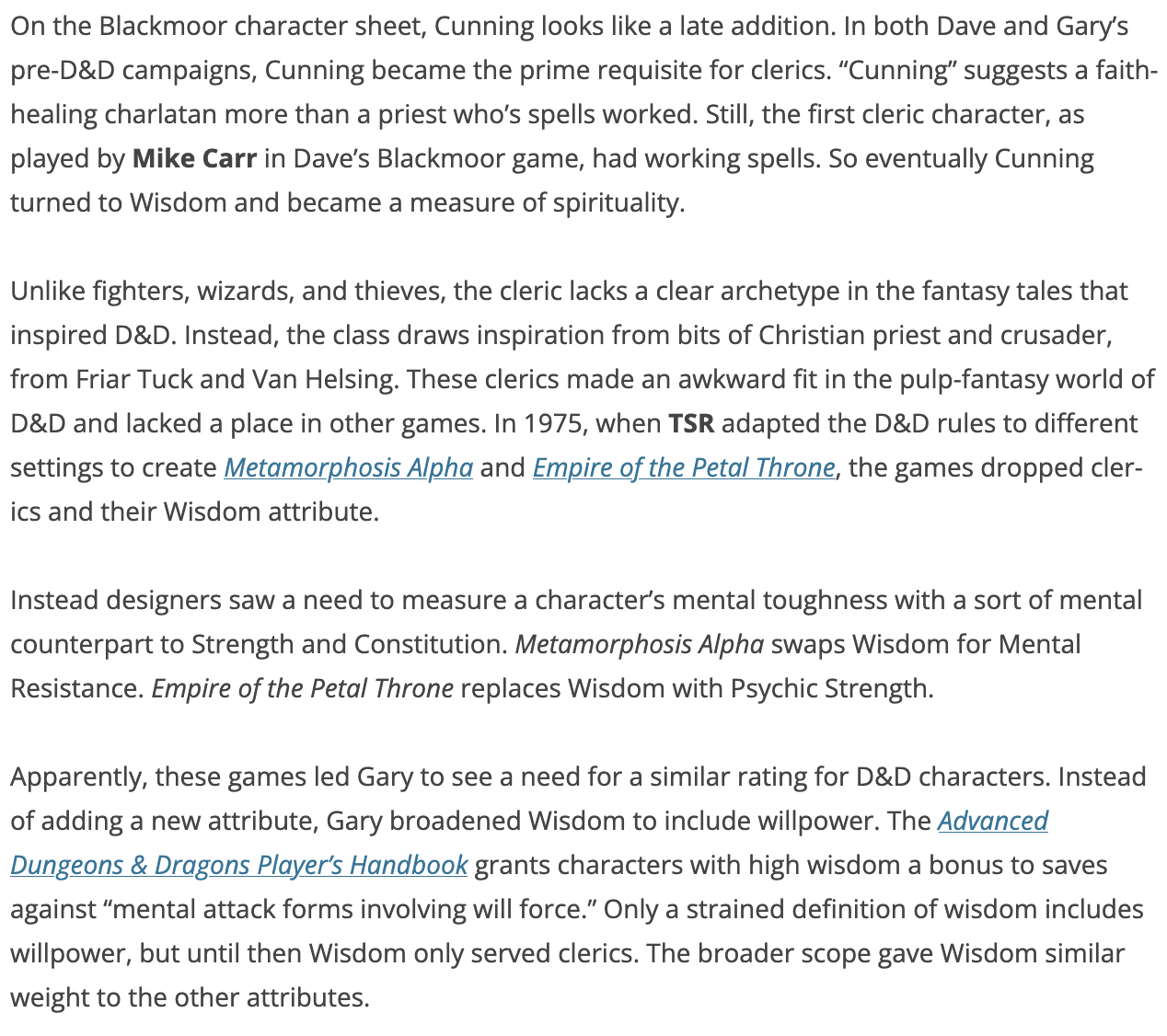

And this is just for the moral question of stealing! Most games use “murder” as their verb of choice, and in reality murder is a universal wrong, regardless of circumstance. That’s not to say games are immoral–the actions therein are all pretend, after all–but they function as nice representational worlds. When one is abstracting reality down to comprehensible chunks, it needs to be based on something. So if a game is already cribbing character stats from Kant (“The worth of worldly wisdom depends on personal wisdom: someone who is worldly wise, but not personally wise, is better characterized as clever and crafty, and yet on the whole unwise.”) they may as well set up a cohesive groundwork for morality from him as well. Footnote: It seems a unlikely that anyone based the distinction between INT & WIS on Kant, but an attenuated coincidence remains a fun coincidence.

It is in the liminal space between the game and the player that concepts pulled from the sharp edge of Groundwork can really shine. Doing a thing is so easily sublimated by getting a thing: Contemporary lifestyle-influencer culture—monetized versions of relentlessly doing it for the ‘gram—is Xbox achievements or PlayStation trophies for normies. Likes and views are weighed and posted, stats are accrued and presented, and personal branding remains de rigueur. As someone who has been playing Roguelike games for decades, watching “progress” be wiped away on an individual run brought out not misery but joy at being able to rise, reborn like a phoenix, cleansed of all past baggage, expectation, or consequence. Starting completely fresh each time turned every attempt its own completely closed game. As Roguelikes abandoned “losable” progress through the filling of meters and unlocking of upgrades even in failure, the joy of a tabula rasa new run becomes the burden of accumulation. People like to collect things: gamer points; trophy levels; website views; account-level virality. When there is a metalevel of progress in a Roguelite, the game is different as you grind along. You are not likely to win on your first try, and you are less likely to lose on your 100th due to in-game character power, not skill or luck or player choice.

How Roguelikes became Roguelites is relevant to Groundwork because Groundwork is predicated on two assumptions: intentionality—why am I doing the things I am doing; and universality—the rules should be the same for everyone, regardless of outcome. Roguelikes structurally mirror both of those premises in ways most games don’t. Starting a game like Rogue or Angband or Dwarf Fortress or even Civilization for your 10th time is the same as starting it for your first time or your 100th time. There is no room to question why you are playing these games, because you can’t have runs where you are trying to do anything but play—nothing “comes with you” to your next attempt. Kant makes the point that in reality it is impossible to know if you’re doing nice things for clout or because you’re a kind soul; Roguelites muddy the clear waters of the Roguelike—are you playing this run to unlock some bits that will make future runs “better”, “easier”, “more fun”?

Games that don’t allow you to save any progress may also engender a feeling of true fear—losing in the game can impact your “reality,” if you aren’t enjoyibg the act of playing the game but just “want to get through it.” Losing some of the finite time allotted to your life to tedious actions is terrifying, though why one might play a game wherein the act of playing feels tedious is an important, yet different, question. Being forced to redo a section all while being faced with the potential that your re-attempt is futile at this point in your game-cycle—does the part I am struggling with require more linear time spent in rote action to power up my character?—is synecdoche for the ceaseless hunger of the treat/reward cycle. Ask yourself: if you’ve hit the level cap in an RPG (or really any game that doles out experience points), do you still want to fight the random battles when you’re not “gaining” anything? What Groundwork seems to me to position itself against is doing things for reasons outside of themselves: the very clear failure of prizing destination over journey. Why play a video game if it has been reduced down to checking something off a backlog, or getting a little stamp that said it is done? Heading to a museum exhibit to make it a selfie background is big business that preys on the desire to collect the intangible; when art has been distilled down to signifier for personal branding, used as shorthand for those browsing our hinge profile or peering into our endless content, we are warping both the intentionality of the art (by reproducing it as mere background fodder) and its universality (by repositioning it as an offshoot of our persona). Are Instagram influencers enjoying their trip to the Museum of Popcorn, or are they simply seeing the wireframe of “this tag will engage more, this background is rare and thus must be collected”? Did the reddit poster that platinumed Ghost of Yōtei within a week enjoy playing or posting more?

However, a finite being, even the most insightful and capable, cannot come up with a clear idea of what it is they actually want…They may want riches; but then, how much worry, envy, and intrigue might they not thereby bring on themselves! They may want knowledge and insight; but that might just make them all the more terrifyingly aware of the ills that they do not yet know about, but which they cannot avoid; or might just burden their desires (which already give them enough trouble) with yet more needs. They may want long life; but who will guarantee them that it would not be a long misery? They may simply want health; but has not bodily discomfort often saved people from the kind of excess they would have plunged into had they had perfect health? And so on. In short, they cannot follow any principle to determine with complete certainty what would make them truly happy, because that would require omniscience.

I talked about this exact omniscience in Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead. The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt dealt with moral choices by making the consequences for your actions attenuated, contrary, and outside the standard telegraphed RPG ideal. And the response from the gaming community seemed to be, “This sucks, I want the “best” ending and I will use a walkthrough to tell me how to get it.” Why would any developer bother making real choice and consequence in games if the vocal outcry that surrounds them is not about telling individual stories but about wanting what has been designated as “best”?

The problem of determining reliably and universally which action would advance the happiness of a rational being cannot be solved; hence there can be no such imperative that would command us in a strict sense concerning what makes us happy. For happiness is not an ideal of reason, but of the imagination, which rests on merely empirical grounds.

How can there be a “best” ending? “Best” for your character? “Best” for you, the player, who is viewing the world from outside and therefor wants it to be the most interesting, even if heartbreaking? “Best” as in you’ve seen everything the game has inside of it, even things that force the character to commit to choices that are contra the POV character’s interests or require the player to reload from hard saves to see different outcomes? And, again, someone else had to write these events, some game designer or games writer had to pull from their own understanding of causality, or universal consequence, or dramatic irony to create what is happening onscreen. Do they have a Kantian understanding of morality, where any “good” action must be able to be universalized, thus even a universe-saving hero cannot remain a hero if they do something where the “ends justify the means”? Any action the hero takes must be an action allowable to everyone else. Functionally, that means killing is right out, and therefore even stopping a world-ending calamity with violence would not be moral.

I suppose you could parse each specific videogame scenario for context–if such-and-such terror is to be wrought on humanity, then violence to stop it is universally allowed by humanity. Very quickly, things can be reduced down to which side of the violence the player is positioned to support; perhaps that is why “chosen one” narratives proliferate. Imagine there is an artifact of great power, like the Master Sword or the One Ring, that is so potent as to be absolutely corrupting. Culture might install a mythos of purity so that it remains out of reach from casual malice. Wrap your immoral weapons of ultimate destruction in layers of obscure selflessness and perhaps they will remain unused. “...[W]e think of a human being differently and in different relation when we call them free, from when we take them, as a piece of nature, to be subject to its laws.” If anyone can use the Master Sword, then no one should use the Master Sword, so we must pedestal the special hero’s special quest so it is seen as the exception to the rule of “don’t murder people.”

Swords are the standard tool for main characters in videogames because they represent no other use than person-to-person violence. Axes can chop wood, scythes can reap wheat, bow & arrow can hunt game animals. Video games (that aren’t Stardew Valley) have an overwhelming dependence on violence (sure, there are swords in Stardew, but I never played it long enough to see one), but the solution video games seemed to reach isn’t, “Vary the actions a character might be able to do” but, “Since you can only do violence, the A button is mapped to sword.” Swords are symbols of person-to-person violence, and can be interpreted as very little else.

sword never changes

Everything in a gameworld has intent buried in it somewhere, and if you are creating a gameworld, you can know the underlying motivation that drives your players–to play with stuff. Creating quests where the player must “do the right thing” for the little fictional people they meet usually ends up rewarding them the most, or best, stuff. Players are continuously materially rewarded for being “nice,” so they aren’t actually choosing morality as Kant sees it, simply being good little piggies snuffling up treats in the most efficient way possible. Think about the first Bioshock: maybe if slurping up the Little Sisters gave you creative, exciting superpowers that were fun to use, and not doing so stuck you with boring and weak gun-violence, there would be some actual moral distinction beyond red-tinged vibes and blue-tinged vibes. You almost never “miss out” on the power curve for being “good” in games. Presenting clear positive and negative moral choices in a binary “kick dog/save orphan” way obscures the fact that every single option, scenario, and event that is programmed into the game typically ends up with the same in-game character advancement—no player is allowed to feel like they “missed out” by being “good,” and surely no team’s moral structure is such that they will accept what appears to be incentivizing players by giving them treats for being straight-up malicious. Things are made boringly clear—this bad action will make your guy grow little horns—because there has to be a pretense of universal objectivity: otherwise, when people do what they think is good and end up with a bad result, their brains will catch on fire and the internet will hear of their mistreatment.

If, in a being that has reason and a will, the real end of nature were its preservation, its welfare, in a word its happiness, then nature would have hit upon a very bad arrangement by appointing the creature’s reason to accomplish this purpose. For instinct would have been better at mapping out the actions and the general rule needed for this purpose, and would thereby have attained happiness much more reliably than could ever happen through reason.

For after they weigh up all the advantages they derive–not just from the invention of the arts of common luxury, but even from the sciences (which in the end also comes to appear to them to be a luxury of the understanding)–they discover that in fact they have just burdened themselves more than they have gained in happiness.

Perhaps you think to.yourself, “But dinaburgwrites.com, what about Undertale?” And to thee I say, “Nice thought but while the Pacifist (I continuously wanted to write this as “passivist” and I think there is some linguistic intrigue to be uncovered there) route doesn’t reward you with the standard RPG level-grind experience-point-based growth curve, it does reward you with engaging and fun and increasingly complex schmup-style gameplay treats.” So there is a reward for being “good,” and the question remains, are you being nice to the little pixel monster people because you’re still the nice pacifist you, or because the player likes the challenge, or wants to see this how this route differs from, say, the standard murder one?

What are we doing, and why are we doing it? This is a question bigtimers like Kant ask about the human condition, but I continuously think about with regards to videogame structure, narrative, and interactability. Every game is a closed system unto itself, with moral variables baked in by people the player will never meet outside of their created worlds. Maybe the developers are guessing at what morality might be, maybe they don’t even recognize they have to create the structure and response of their little closed universe: “[I]t takes no skill to be understood by all and sundry when one renounces insight into the heart of things.” But since game developers add the motivations—do a nice thing, get a nice item—then gamespace is a unique place where a person could create a Kantian groundwork for the metaphysics morals where doing a nice thing gets you absolutely screwed over in the game. Only then would it be clear that the player is being kind simply to be kind and not to reap the tangible rewards of kindness.

Unless the player is streaming, and their kindness is viewed, catalogued, and monetized to their benefit.