Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic—and What We Can Do About It

by Jennifer Breheny Wallace

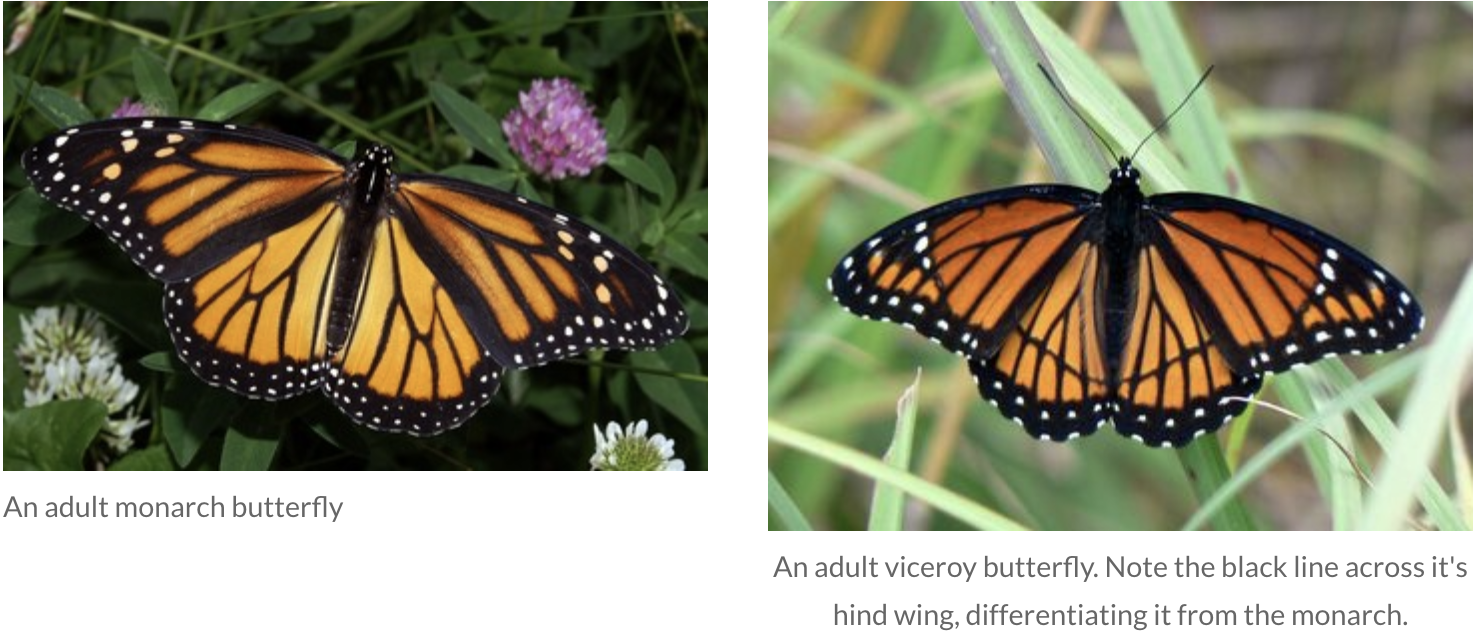

I do not know why I do this to myself. Look at that title. Just look at it. Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic–and What We Can Do About It is like a Viceroy Butterfly—the subtitling has an outward appearance that tells birds that this book is not a healthy snack, but it only closely mimics the actually-toxic Monarch butterfly to fool predators into avoiding it. Yet, like some sort of maniac, I cannot help but roll the dice and put it in my mouth.

Speaking of things not to ingest, I am not sure anyone can trust the author’s judgment after she let this happen: “..we met for fish tacos in Phoenix, Arizona.” Those tacos could not be good, right? Not good enough to put in the book. I can’t conceive of a world in which they were even edible. How far is Phoenix from any large body of water? Yikes.

In all seriousness, the thing with Never Enough is that I didn’t hate it. Like the Monarch imitators, the warning signs are there mostly just for show. Never Enough is not malicious like Drunk Tank Pink or misleading like Drink or tedious like Quiet; it feels like it came from a place of genuine, personal interest from the author, just bathed in all the trappings that make this genre terrible.

Honestly, the book could have been fun if it were just personal essays and a bunch of interviews instead of anecdotes strung together by lose threads of unexamined claims from weak pop-science resources. I also don’t mind advice—the author is a member of the affluent cohort that the book targets as an audience, after all—but the advice herein wants to be universal in the same misguided way that cherry-picking small p-hacked social science studies to “prove” conclusions wants to be real: the book has a real conclusion-in-search-of-a-hypothesis vibe.

I recently read The Guest, and I can’t help but imagine that the Hamptonites Alex was infiltrating would read, or have had their assistants read, Never Enough. Maybe it would just be loose on an end table somewhere, implied beach reading that signifies self-actualized betterment, even in leisure, just by being there. The whole book can be summed up as such: “You, the wealthy folk, might feel a threat to your personal social status if you went to Yale and your kid doesn’t get in. Therefore, the drive to pressure the crap out of them to follow your life’s golden path is tempting. All the other Yalies that moved to your zipcode do this too, creating a toxic bog into which your children will drown.” The advice: “Don’t do that.” There, that’s the book.

And that’s pretty good, I have to say, for a book like this. I get that this book is not for me, it’s for the moms–and as a stay-at-home dad that constantly gets praised for doing literally anything within the sphere of childcare, I feel confident (and sad) that anything about raising kids is default-targeted at moms, but given how our country is socially conditioned this is not a radical statement–that are flipping their kindergartner’s coats backwards so the zipper runs up their spine and little grabby hands can’t reach it after said coat hits the ground twice. Lady, it is 55* out and your kid is running and climbing like an American Gladiator. Listen to you kid, they’re hot. You can’t control them forever!

Seriously, the book knows it’s for the moms:

Decades of resilience research makes this clear: a child’s resilience depends on their primary caregiver’s resilience. At home, the primary caregiver is usually the mother. This directive, Luthar said, has turned child development upside down. To help the child, first help the caregiver.

While I agree that moms are completely overworked in most American households, it’s not hard to soft-peddle self-care that is specifically built to assuage your target audience. It feels a little gross for a book that is functionally reminding the reader that their kid is not an extension of themselves to take care of their own wants first. Perhaps, though, the audience for this book is not just the affluent but the strivers, who do need a hobby beyond scheduling acrosports and swimming and soccer for their toddlers while making lunch and dinner and laundry et&c.

So the book does this one good thing pretty well: it reminds you that your kid is not an extension of you. Great. How well does it stay on message? How much does it gently stroke the egos of the reader, remind them that they, as a person that picked up this book, are one of the good ones and other parents are the ones that foster the toxic pressures?

“Some parents believe that not just any good college will cut it–to maintain our status, our kids must get a particular sweatshirt.” First, the word “some” modifies parents so no one gets their feathers ruffled. Then, the choice of the word “our” is doing a lot of heavy lifting. Weird inclusive/exclusive balance, but you gotta make some contradictions if you don’t want to break any eggs. Second, the minimizing synecdoche of “college” to “sweatshirt” is cheap rhetoric when used to counterbalance the over-inflated importance the author claims “some” parents put on “our” kids. Yuck. Here’s the rub, and why Never Enough can tackle a relatively tangled issue while letting everyone walk away feeling pretty good: there is simply no exploration of the social structure that landed us here, no history of higher education or trace mention of Veblen and the rise of secondary education as acceptable conspicuous consumption for a leisure class breed under the auspices of American Exceptionalism and grounded in a puritanical faith that hard work begets wealth as a sign from Christian God that you are righteous.

The reason why an “elite” sweatshirt matters to some parents is because it has the imprimatur, the continuance, of a faux-aristocratic lineage mandated by the gods of commerce and hard work. I am quite surprised that a modern book cannot trace a line through history and end up reminding–or educating–the intended audience that your kid’s college functions the same way, whether you mean it or not, as any another capitalist adornment. The cost of the Ivies is an intended gate–they’re “selective” through pricing people out. This type of exploration is not approached by Never Enough: the reader will be told not to push your kid to go to Williams from the comfort of your coffee table-morning commuter suburbs and school districts with massive tax bases, but not really why. Still, no matter how we get there, the point remains relatively valid: don’t overwork your kid.

Many of the problems I had with Never Enough began and ended with this lack of “why.”

And now we get into the research part of the book, and it falls down, and I get petty.

“Experiments have found that people are less willing to own up to feelings of envy than they are any other emotion.” Ok, please tell me about them. No? Oh, okay, let’s check the citation/reference page. Nothing? Oh, okay, so that’s just a thing we say now. Got it.

What is the reference page for, if not telling me about experiments you’re vaguely gesturing toward? Oh, the DFW This is Water commencement speech gets a cite? Let’s see how it was used:

So when we talk about the waters of achievement our kids swim in every day–the waters that erode their mattering–these skewed metrics of performance are perhaps the most difficult for our kids to see and name. It’s the water they swim in, invisible because it’s all they know.

That…you don’t even mention it! Why reference it?! There is a “further reading” section–put DFW there. I guess the reference page is technically a Notes page, so the “citations” are just a politeness. There aren’t even page numbers attached to the Notes.

That little section about DFW and fish does have an original line that hits, though– “...[What we’re doing is] causing kids to have to break their necks to distinguish themselves within a very narrow band of excellence.” This is right. This is, in my opinion, the core the book gets right, if only for a sentence. For example, my wife is a phD scientist. Most of the people she knew during school were getting their phD. Most of the people she works closely with after school have their phD. She does not consider it a rarity to be a phD level scientist. I practiced law for a bare handful of years. In law school, most of the people I knew were law students. I do not consider it a rarity to know a lot of lawyers. Most people I have met outside of law school or legal firms personally know exactly zero lawyers. Zero scientists. These insular communities exist and when you’re inside them, they feel like the whole world. Now image being a teen–when your understanding of the larger world is basically zero–and having your whole entire world be one of affluent competition. Yuck. So points for acknowledging this.

There are many more notes I made in the margins to signal a statement of fact based on no foundation: “But today, rankings feel more urgent and ever present.” To whom? Why? These things are just tossed off. “Research is clear that student outcomes are stronger when they are genuinely engaged with what they are learning…” Clear, maybe, but not cited! “Researchers have a hypothesis: In a hypercompetitive, individualistic society, you must be narrowly focused on your own goals just to make it.” Dude, you can’t report on a hypothesis and then run with it like its real!

To circle back to the book’s most oblique “citation,” the foundation of toxic achievement culture is so much in the water for the author that subjective things must feel like they’re obvious and true. But we all don’t come from the same gated Country Club. Maybe that is who the book is for, but it doesn’t even attempt acknowledge, let alone to talk to, any other demographics.

In the end, not matter how soft and gentle Never Enough tries to be to the reader, it continues to uphold the same selective pressures as any ‘competitive’ program: if you don’t have the “right” foundation, it’s not going to waste any time catching you up. There are always books about Community College to fall back on, right?