The House of Mirth

by Edith Wharton

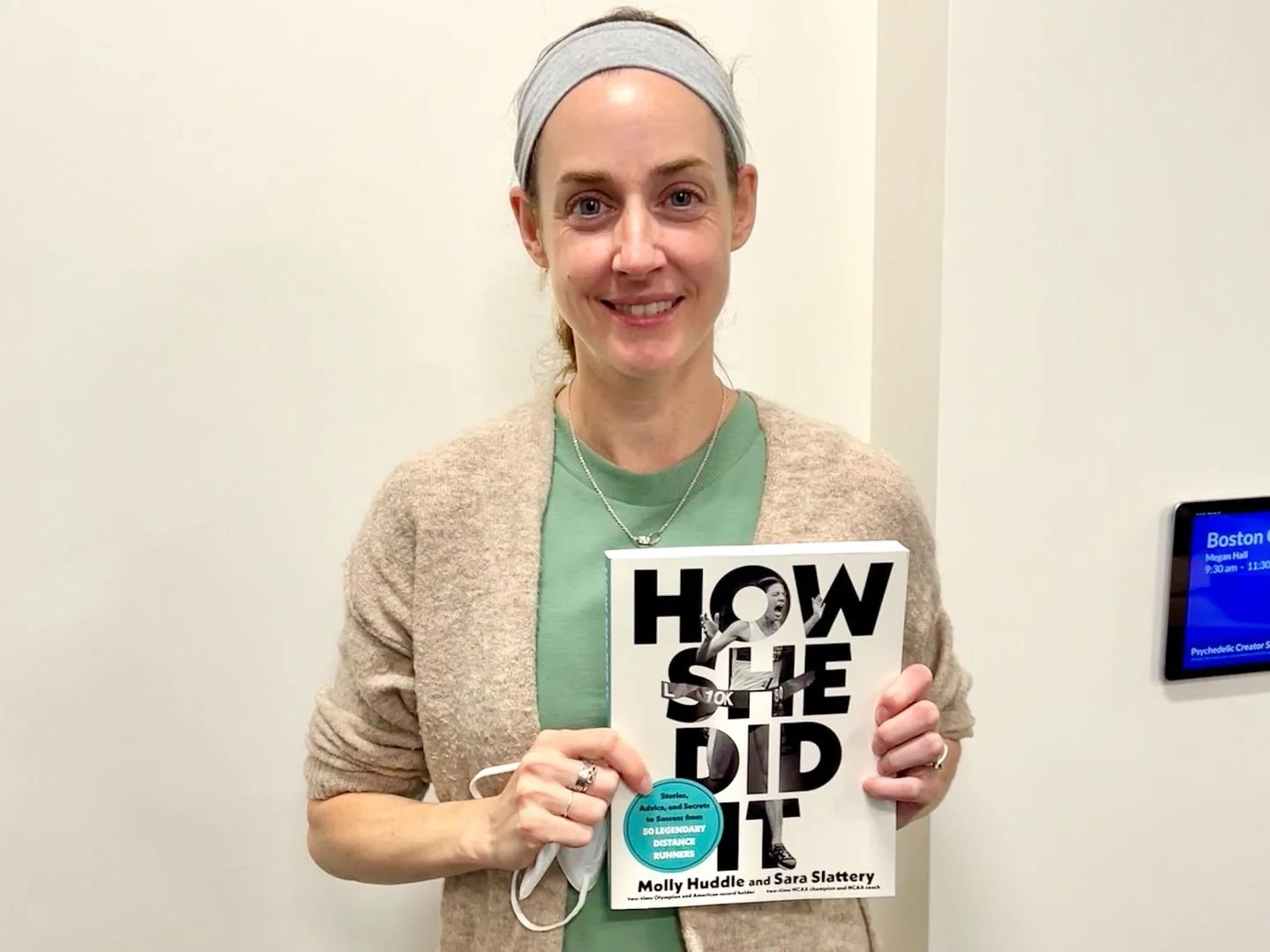

What must it feel like to write a novel when you know The House of Mirth already sits on library shelves? My guess is that it’s similar to why I keep lacing up and hitting the streets of various major cities to run marathons—finishing 6135th out of around forty thousand isn’t bad, but there is no world in which I approach a start line of the Chicago marathon and picture myself winning. So it is with putting a book out in the world when you know someone could be reading about Lily Bart; no one is going to even get close to Edith Wharton. She’s the Molly Huddle of novel writing.

At the close of Mirth–wherein I spent the final dozen pages saying, “Aah dude, she’s going to die” to myself over and over, and then, of course, she did, and then I did what tiktok would call Level One Crying (a misty eye wherein someone could plausibly ask, “Hey, are you crying?” and it could go either way)—I knew I needed a break from fiction. It felt unfair to burden the next book with trying to keep up with the Joneses. Hey, do you know where the expression “keeping up with the Joneses” likely came from? If you guessed Edith Wharton created it, you’re…almost right: “Edith Wharton’s mother was the former Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander, and her father was George Frederic Jones (it is said the expression “keeping up with the Joneses” referred to them.)” Again: you aren’t going to beat her in a marathon, my dude. She is the Jones that we, as a society, have been “trying to keep up with” for like 140 years.

It is possible–really, truly, non-hyperbolically possible–that i will never read a book better than Mirth in my lifetime. Living under modern capitalism is a sickness that produces a “growth at all cost” mindset, and it can be slightly jarring to realize I might have already experienced the peak of reading fiction for pleasure for my entire life. But, again, I don’t think I’m going to win marathons and I still run them, so I think I’ve come to terms with the concept that things don’t have to be perfect to be worth doing; I am pretty sure I’m ok with reading books that place 6135th on the shelf. However, if I had read Mirth in college–if I was the same person then as I am now (I am not), if I knew how to read it in college (I did not)–I would have dedicated my studies to it. Honestly, I am slightly grateful for the travesty of literary education that didn’t lead me to it for forty years. It is an immaculate novel. 118 years old and ageless. Applicable to so many paradigmatic concepts of social order. Would I have known enough to see its brilliance earlier in life?

It was before him again in its completeness–the choice in which she was content to rest: in the stupid costliness of the food and the showy dullness of the talk, in the freedom of speech which never arrived at wit and the freedom of act which never made for romance. The strident setting of the restaurant, at which their table seemed set apart in a special glare of publicity…emphasized the ideals of of a world in which conspicuousness passed for distinction, and the society column had become the roll of fame.

Current American reality so completely mirrors the trappings of the turn of the (last) century–search for “new gilded age” and you’ll find hundreds of articles about right now–and Mirth sits alone as a book that spells it all out for us: the emptiness of material culture—“Of course one gets the best things at the Terrasse—but that looks as if one hadn’t any other reason for being there: the Americans who don’t know anyone always rush for the best food.”—; the personal impotence in overcoming structural oppression—“How impatient men are!” Lily reflected. “All Jack has to do to get everything he wants is to keep quiet and let that girl marry him; whereas I have to calculate and contrive, and retreat and advance, as if I were going through an intricate dance, where one misstep would throw me hopelessly out of time”—; the shadowy obsequiousness of strivers and hangers-on for a taste of idle luxury—“Everybody know what Mrs. Dorset is, and her best friends wouldn’t believe her on oath where their own interests were concerned; but as long as they’re out of the row it’s much easier to follow her lead than to set themselves against it, and you’ve simply been sacrificed to their laziness and selfishness.”

There is no more scathing indictment of culture than when “conspicuousness passe[s] for distinction.” It’s not exactly clear to me what Mrs. Wharton actually believed “distinction” meant—she’s not a perfect person, of course, though she is immensely insightful—and it does seem that the distinctions between money, wealth, and class come up quite a bit:

“…the only way not to think about money is to have a great deal of it.”

“You might as well say that the only way not to think about air is to have enough to breath. That is true enough in a sense; but your lungs are thinking about air, if you are not. And so it is with your rich people–they may not be thinking of money, but they’re breathing it all the while; take them into another element and see how they squirm and gasp!”

A hard edge of the novel revolves around buying a way into the arbitrarily elite circle of American aristocracy, and Lily seems to represent old money—without the money—as she slowly begins to realize that it is money alone that ever keeps the leisure class aloft:

The inability thus to solace her outraged feelings gave her a paralyzing sense of insignificance. She was realizing for the first time that a woman’s dignity may cost more to keep than her carriage; and that the maintenance of a moral attribute should be dependent on dollars and cents made the world appear a more sordid place than she had conceived it.

What appears to the paradigmatic virtue of puritanical hard work begetting wealth is left to wither on the vine—there is no leisure without the accompanying capital, and the wealth itself can catapult nearly anyone into the realm of the virtuously rich. This myth extends its grubby, grasping hands into nearly every aspect of popular cultural, and it is a large part of what gives Mirth its intensely modern feel.

Example: have you looked at the American Girl Doll catalogue lately? No, probably not, but I have. And it is selling the same type of luxury-for-luxury’s sake that curated instagram feeds use to lure people into spiraling debt: everyone you follow becomes another Jones with which to be kept up:

You know how dependent she has always been on ease and luxury–how she has hated what was shabby and ugly and uncomfortable. She can’t help it–she was brought up with those ideas, and has never been able to find her way out of them. But now all the things she cared for have been taken from her, and the people who taught her to care for them have abandoned her too…

It’s not even sneaky about it. The dolls are flying first-class! They will spend their copy-editor/social media manager paycheck on a weekend in Ibiza, post a slew of pictures of themselves at their resort hotel pool, and then go back to their 2-persons-in-a-380sq-ft West Village apartment. That apartment is not shown in the catalogue, nor the mounting bills from Klarna and afterpay. I’d say I’m quite shocked there is no Lily Bart American Girl Doll, yet, but essentially, they all are. “She can’t help it–she was brought up with those ideas.”

I am not immune to this type of subtle structural emphasis; my dolls did not teach me how to layer appropriately for fall on Martha’s Vineyard, but the Ninja Turtles did teach me that storm drain grates and sewer covers are too heavy for a nine-year-old to lift.

Beyond the immense cultural relevance in the specific details of the novel, there is a structural elegance to the writing that just does it for me. I am aware that style is to a taste, but to me, this is it. The writing so beautifully rendered and clear without being boring. The very foundations of the novel are made unique by their distinction from modern writing conventions. Not only is it not a wry first-person account or chapter-based third-person limited structure, the narrator is truly omniscient. And the omniscience is not one of fiat: it juxtaposes quite clearly and concisely both what a character thinks is motivating their action and what is truly happening in their heart and mind. To those weary of the ever-present trope of unreliable narrators–which, granted, the first time you realize authorial voice can lie to you is a mind-bending moment–Mirth is a breath of fresh air. It is like how everyone realizes the Mona Lisa is astonishing (so famous!), and then you get older and think its overhyped (so tiny?!), but if you’re an artist you can see a thousand small details that truly make it a masterpiece (golden ratio!).

Lily felt a new interest in herself as a person of charitable instincts: she had never before thought of doing good with the wealth she had so often dreamed of possessing, but now her horizon was enlarged by the vision of a prodigal philanthropy. Moreover, by some obscure process of logic, she felt that her momentary burst of generosity had justified all previous extravagances, and excused any in which she might subsequently indulge. Miss Farish’s surprise and gratitude confirmed this feeling, and Lily parted from her with a sense of self-esteem which she naturally mistook for the fruits of altruism.

The explainer of “Lily thought this, but really it was this, and here’s why” could be so painfully dull. However, because the insights are tied to an emotional comprehension that is grounded not only in the fiction but what feels like our actual reality, and that reality is recognizable on sight but often hard to unearth on your own, it feels revelatory. Of course people act as though a single kindness wipes away prior selfishnesses! And frees you up to commit more selfishnesses in the future! Who looks at themselves honestly enough to admit such justifications? Not Lily Bart, certainly, and likely not the reader, either. But Edith Wharton sees. She knows not only what you do, but what you say to yourself to justify it. For an unfair—because it is YA—but simple—because it is a known entity—comparison, think of the Harry Potter books: the character actions make very little cohesive sense (why is Snape mean to Harry?), and their stated justifications don’t really seem realistic (because he had a crush on Harry Potter’s mom?), and their actual motivations are never unearthed (because ????), and if they were, could they possibly seem like true insight into the human condition (because what does the action of child endangerment represent)? Mirth uncovers the whys and wherefores of human interactions, and it looks great doing it.

Simply recapping the plot makes the book feel flighty or even pointless. A grade schooler could sum up the arc of the action thusly: “Lily is shallow and wants to marry one of the hyper rich because she likes being pampered. But she keeps messing up and no one will marry her so she dies poor. The end.” This unfortunate and short view proliferates on certain book-centric websites. Curiosity got the better of me, and I felt compelled to see what the one-star consumer reports on said website wrote about The House of Mirth. I should have known that the vast majority of people who didn’t like Mirth didn’t finish it, and the remainder who clung on just to spit venom “couldn’t relate” to Lily Bart. “Hard to empathize with someone like her.” Friend, maybe you’re just shit at empathy? Flippancy aside, I must ascribe a systemic failure to both that line of thinking–finding someone “relatable” is not required of fiction; one need not self-insert to enjoy a book–but Lily isn’t the problem. The society that “...was the life she had been made for: every dawning tendency in her had been carefully directed toward it, all her interests and activities had been taught to center around it. She was like some rare flower grown for exhibition, a flower from which every bud had been nipped except the crowning blossom of her beauty…” is the problem. If you can’t directly empathize with someone concerned with marriage and fashion and high society, fine: but that means your reading of the text is one-dimensional, your understanding of the human condition is surface only. If you cannot even approach the realization that Lily is a product of her environment–that the way you were raised and what you were taught to strive for might be at odds with what you actually want–the failure is in you, not in The House of Mirth. If you need to relate to Lily Bart to find the book worthwhile but cannot peer through the petticoats and vanity to the chains and cages that restrict everyone (mostly women) in social and financial bondage structures, you’re the problem.

Affluence, unless stimulated by a keen imagination, forms but the vaguest notion of the practical strain of poverty. Judy knew it must be “horrid” for poor Lily to have to stop to consider whether she could afford real lace on her petticoats, and not to have a motor-car and a steam-yacht at her orders; but the daily friction of unpaid bills, the daily nibble of small temptations to expenditure, were trials as far out of her experience as the domestic problems of the charwoman. Mrs. Trenor’s unconsciousness of the real stress of the situation had the effect of making it more galling to Lily.

That’s you. You’re Judy.

If you skipped to the end for a plot recap to plagiarize get ideas for an academic essay, congratulations, you have a great teacher that assigned you an amazing book. Also, kudos for not just using gpt-3 to write it for you. You are well on your way to understanding why people who can’t possibly win marathons still run them, and why people whose books cannot possibly be better than The House of Mirth still write them. You are on the path that Lily couldn’t quite find—“But we’re so different, you know; she likes being good, and I like being happy."—that “good” and “happy” are, in fact, dependent upon each other.