Automatic Noodle

by Annalee Newitz

The worst thing I think I ever wrote was my 2017 review of Sourdough. I was intensely unfair to that book, often factually incorrect in my assessments. Worse yet, I was simply mean for no reason. It is my touchstone for what not to do. So when I don’t particularly gel with a book, or find myself nitpicking in preparation to argue ways to justify my taste or convince a hypothetical person that I’m factually correct in my subjectivity, well, I unleash a little of that hot Sourdough shame that’s always floating around in my head. So it was that I found myself with Automatic Noodle. I didn’t like it much, but it is fine.

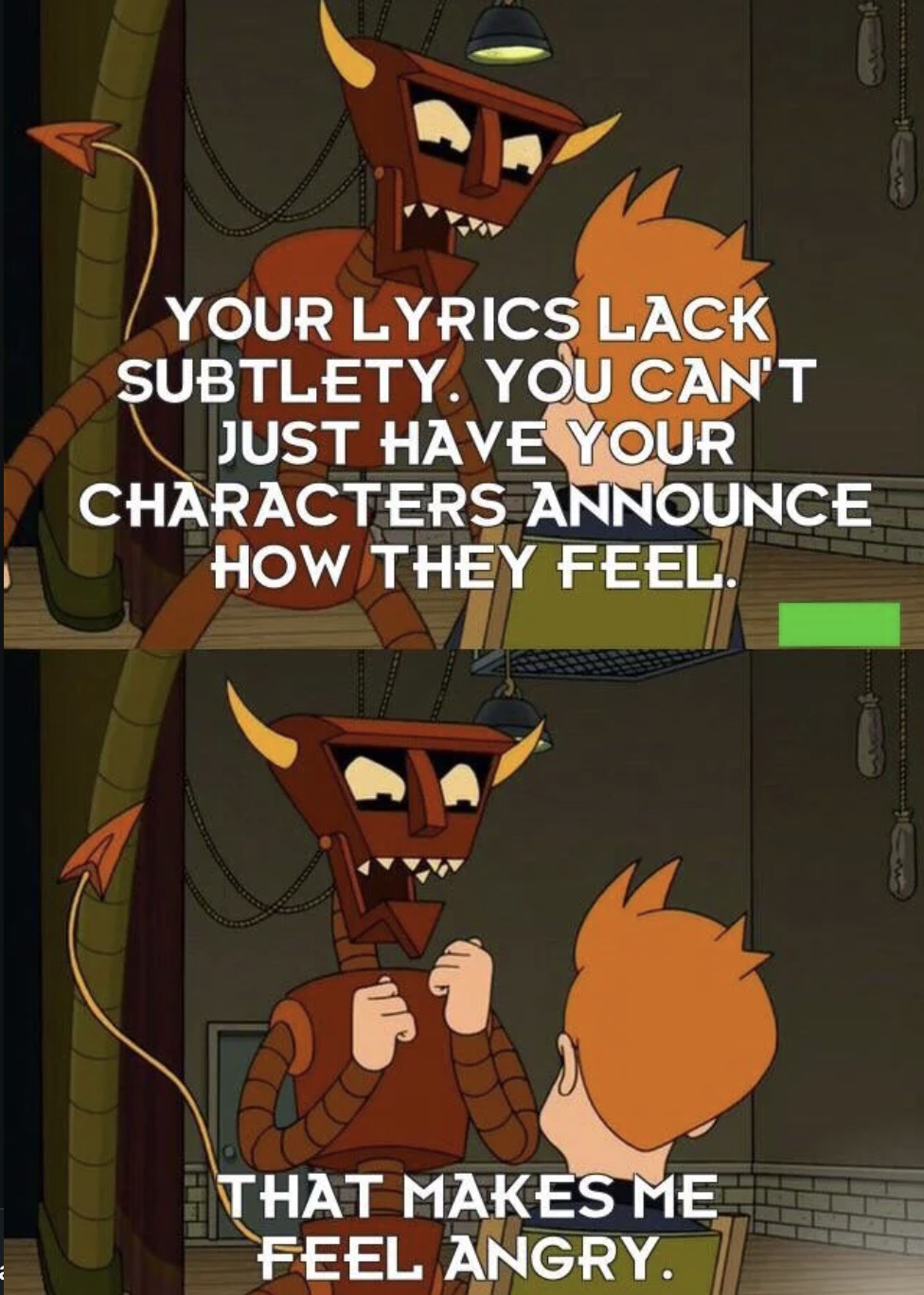

So let’s start with the good parts: any underdog story where a cast of misfits shoulder society’s unfairnesses and rise to success and/or happiness will inevitably move me to tears. Literal, blurry-visioned tears. The robots in Automatic Noodle are like one-to-one Jim Crow-era freed slaves, given partial civil rights and confronting structural inequality. It’s not subtle–it is melodrama–and when nice things blossom for this team of scrappy survivors it pokes at my heart, and the heart of what storytelling can be; good things blossoming in bad situations.

It also has some cute robot lines, like “Will it require any expensive ingredients or equipment? Because if yes, then no.”, a deployment of robo-logic that didn’t feel forced. One SF-insider reference, to the shoreline being at 35th, is stated without a big nudge that sea-level rise has consumed a dozen or more blocks from the current city layout. It felt nice to be trusted to know the metes and bounds of the Outer Sunset or be okay with missing the joke.

For me–and I know tastes differ, because I’ve seen Automatic Noodle on Staff Pick shelves all over the city and my own sister called it her favorite read of the year–this book in general doesn’t hit. When I read Nona the Ninth I mentioned that it had snarky dialogue that toed the line between fun and unpleasant. I enjoyed Nona. Noodle did not work for me:

“People could watch us making the noodles, the way everybody watches the chef at Xi’an Spices. I’m not as good as she is, but it would be nice to show people what we mean by San Francisco style. Robot rizz!”

and

Sweetie stuffed the oil in her backpack and raced to the escalator so she wouldn’t have to hear the rest of the cringe.

In these specific examples its the slang that flopped, too in-time not to betray the text. It would be like spotting a hyphy, a fleek, a groovy: too rooted in their moment. Rizz has already been replaced by plus whatever aura, as far as I can tell, but the deployment of unfortunate slang is more metaphor than crime; the text is a bit too compressed for me, overworking large sociopolitical moments into simple shapes.

Each of the characters felt like a kernel of an idea spun out into an an allegory for a disenfranchised group: the “traditional beauty standard” robot that feels empowered when she can dress and style herself in a more “natural” way; the large military robot that “...wasn’t sure what pissed him off more: having to put on a show of unctuous politeness to avoid being snubbed, or the fact that he cared enough about this woman’s opinion to do it.” When they succeed with their restaurant, though, cue my own big feels because I desperately want a more equitable and just future. I just didn’t feel super interested while reading this attempt at showing the struggle.

I do think having an assembly-line robot that is mostly a torso with arms that, once freed, becomes inspired by youtube cooking videos where the camera-cropping exclusively shows a human torso with arms is pretty clever.

But single, flat concepts do not a novella make. The group of unhoused kids announce to each other, “This place is nice and isn’t kicking us out” while eating at the robot restaurant. It’s not subtle.

I like blatant melodrama well enough, but Automatic Noodle didn’t give me much to chew on. I was just sort of nodding along, pleased when the business thrived. The major conflict was resolved through the idea that the disenfranchised could find a way to rise above through, well, capital accumulation. If you look at the plot long enough, its core exposes itself as a fin de siècle (this is appropriate for the late 1990s now, right?) concern about reversing white flight, where urban renewal is allowed to driven by small minority business ventures rather than massive multinational conglomerates. Dare to dream.

This is not a revolutionary text. It is in fact kind of a retrograde up-by-your-bootstraps story, less about remaking equitable political and cultural structures than about carving out space to join in the fiscal absorption of the status quo. Yay for sentient creatures being treated as part of the moral body; nay to success being defined through business acumen and financial gain.