Twitterbots: Making Machines that Make Meaning

Tony Veale & Mike Cook

Well.

This book was meant to be my victory lap: I began reading Twitterbots: Making Machines that Make Meaning while I was deep within a month-long interview to write for an AI chatbot language that I, somehow, already had experience writing in—kismet, found.

But in the end it was kismet, lost. Even before that option fluttered away on tiny bird wings, I began to feel trepidation toward Twitterbots: “Why am I reading about a subject I’m about to spend most of my time working on?” It went from interesting hobby to potential schoolwork. The constant refrain directing the reader to the authors’ web resources echoing from each page didn’t alleviate the scholastic feel. But those resources—equal part repetitive in mention as useful in practice—couldn’t break up the meaty parts of the text:

Though human creators benefit from the same word-of-mouth marketing by avid followers, we don’t want our bots to simply ride on someone else’s coattails but to become an active part of the co-creation process.

Like Duchamp recognizing the aesthetic merits of a lowly object that many others have scorned, we become connoisseurs of the generative object trouvé when we acclaim these accidents of bot meaning.

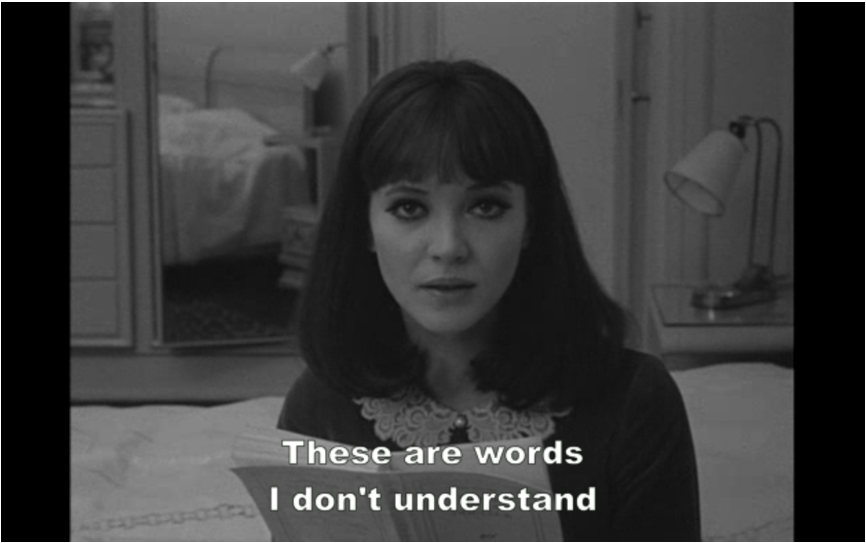

The authors have a good handle on referentials. They are clearly skilled with bot programming, but equally able to cite Duchamp, pull poetical Reagan quotes, or dissect Godard.

They even tell you why:

When it comes to language reuse, we are all as adept as the most cynical hack, often preferring quotes from Shakespeare (fancy!) or classic movies (cool!) over our own bespoke metaphors, similes, and jokes. Even when we take pains to turn an original phrase, it is hard to avoid the lure of the familiar. But this is exactly as it should be, since communication benefits from eye-catching novelty only when our target audience understands or appreciates this novelty.

Engagement with and understanding of more than just technical breakdowns makes for text that is often engaging regardless of your proximity to bots, AI, or ML writing. It is interesting to see how tech-minded people with a firm grasp of the humanities—rather than the near-exhausted trope of the literary stodge trying to make sense of technology—engage with cultural source. The written word isn’t treated as mere grist for the GPT-2 mill.

I personally love twitter. I block frequently and never get piled-on because I never tweet anything but links to my book reviews. When I look through my past timeline, I am delighted by what I’ve chosen to retweet. It is a really privileged niche I’ve carved out for myself, where I don’t need to see anything outside of comedians (that I think are good), smart people (that I think are good), and visual artists (that I think are good). Maybe you need to do more because you’re selling your services or are a public figure, but I am not and so I don’t. I recommend it.

And when I do see most twitterbots, they’ve been filtered by the aforementioned people that I believe to be smart. These are people I’ve already opted in to following. Thus, their retweets—bot-related or not—are double-filtered choice selects pulled from the chaos and suited to my taste.

I broke this rule, once and began following a bot directly: Magical Realism Bot. Time and time again, I saw it retweeted from a human, became enchanted, and moved on. Eventually, I went straight to the source, a regret I will live with for eternity. I should have trusted my cultivated layer of protected tastemakers: It did not take long for the seams on Magical Realism Bot to begin to show. So much nonsense. Too much, for me. I suppose that’s the lesson of Twitterbots: I’m grateful people are out there engaging with bots that spit out endless streams of text, but I’d prefer a more curated experience. And you, lucky review-reader, are to be borne on the back of my labor.

This is not a casual read. I can visualize Chapter One being a supplemental text for a mid-level Lit Theory class that needs to touch on automated proliferation—Borges’ The Library of Babel is used to great effect, as is Clarke’s The Nine-Billion Names of God—but no one needs to scour the rest of the pages for insight unless they are planning to build out some sort of bot. Or if they were interviewing for, say, an AI writing position. Just an example off the top of my head that I thought of for no reason in particular.

Twitterbots is a smart book. In depth. Sometimes technical. The only time I outwardly found myself in a prima facie disagreement with what was presented on the page was hardcover p. 284; it exhorts a bot creator to, “in the words of Leonard Richardson, ‘always punch down’.” That has to be a typo: beyond the fact that punching down is a jerk thing to do and exactly the opposite tone from the rest of the book, the prior Leonard Richardson citation two-hundred pages earlier is to his essay titled Bots Should Punch Up. Calling back to this fact was a simple matter—there is a strong index, which I love in non-fiction. And, as a first for me, Twitterbots contains a bot index so you can quickly search the text for any mention of a particular bot. Beautiful, I imagine, if you need it.

It falls into the category of specialty non-fiction—books like Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, or Grains of Gold—that I don’t really recommend anyone else read. Skim, maybe, or excerpt if useful for some pedagogical or autodidactic reason. Are you making a twitter bot? Would you like to? If yes to either of those questions—even a tepid “maybe,” honestly—this book is a resounding win. If not, well...twitter.com is a free website. Curate yourself a deep and endless scroll.