Lurking: How a Person Became a User

by Joanne McNeil

Graduating from high school a single year prior would have substantially changed my experience. Even beyond the natural “but for” causalities inherent in a hypothetical life: sire I’d have different classmates and curriculum if I shifted around my timeline, but delaying a year—rather than skipping one—would have still given me a fundamentally similar experience. You see, I started college ensconced by the false pomp of the millennia—after a dozen years of public education that was steeped in being the “class of 2000”—and this did more than simply tie a Y2K futurenaut aesthetic to us from grammar school onward. We were, as proudly announced by my state college, the first class to have individual broadband access in the dorms. This one real, hard, existential change divided a generation of college kids more than any other.

What was it like to have lived just beyond that digital boundary? That stark dividing line between 56K–if you were lucky enough to even have had a PC and internet at home before college–and being perpetually connected, with no parental checks on your usage, was intense. I can barely picture having to go to a computer lab to get online, let alone simply type up a paper there. And even with frequent nostalgia-traps bubbling to the surface in popular media, I can’t find an ARG or immersive experience interested in recreating what it was like to be in school when computers were possible but not quite common enough for everyone to definitely have one. I’m simply not sure what college was like before every dormroom desk was burdened with a Dell, or what to do when your dining hall experience didn’t begin with checking AIM away messages to see who’s down there eating waffles, or that if you played enough rounds of freeware Snood, the math in the poems politely asking you to pay would round your “cost per game” down to $0.00. No one’s writing books about what people did before Counter-Strike with their roommate, or how the online matchmaking (powered by gamespy) tended to find the closest and fastest connections, which meant you were probably playing someone else and their roommate, so a well-placed grenade to finish a match could elicit cries of sadness that pinpointed the precise dormroom of who you were battling across the virtual de_dust. Not yet, anyway.

What a heavy curtain that single year was: the Sophomores, Juniors, and Seniors above we millennial Freshman lived lives so untethered from the great pulsating mass of technological connection as to be a fundamentally different experience. Did they go home the summer of 2000 and sweat with anxiety because they were no longer connected to the wider world? That feeling of loneliness—not being surrounded by peers physically, and not even being surrounded by their digital ghosts—was heartbreaking to me, a feeling I can still remember more than twenty years later. Was that the first itch of internet addiction? Regardless, the next few tech revolutions that bifurcated education were less infrastructure and more self-directed–when laptops pushed their way into academia I was in grad school. I watched people play emulated Zelda 1 during Con Law, just because they could. Arguably, WiFi access points are infrastructural shifts in the same manner as broadband—I can conjure up a student writing about my experience in the same way I can vaguely fill in the darkness before my time: “I can barely picture having to go to sit at a giant computer at your desk in your dormroom—rather than a coffee shop or park or something—to do anything online, let alone simply type up a paper.” But the sea change of WiFi laptops and ethernet cards have been slightly obviated by the mass proliferation of smartphones and dataplans—or perhaps I am just too old to see what a shift they were to the landscape—but there was no cable broadband backup plan in the Y2Ks.

Lurking: How a Person Became a User will ask of you this type of introspection: how does my life tie to the internet, how has it shaped me, and why don’t I know what motivates the lords of digital space that chain me to it? The book is clever in reminding us that we were frogs in the pot of online culture—the shift from tight community spaces to invisible and all-encompassing substrate was gradual, and subtle: “AOL’s lasting influence is that it disentangled the identity of a general internet user from any kind of subculture or aesthetic.” As a book, it is an early car on the road of what I have to assume is poised to become a traffic jam–‘net nostalgia is shifting from WELLers and Phone Phreaks to your mom’s RuneScape friends or the time a commercial actor messaged you on MySpace because you ironically juxtaposed her with Clytemnestra as one of your “Heroes” in that data box.

I love to read and reminisce with my follow very (or even just slightly) online peers. Even things from this era that I didn’t engage with have a patina and sense of lost possibility that makes them interesting:

Friendster was the cutting edge of nothing, a utopia for no one. Users let their guard down on it because it was a novelty and nothing more. It arrived with no grand message about democratizing society. There was no lofty claim that the platform conjured up a magic world post-race or post-gender. It was a stupid website from a stupid company, nothing more than a boredom antidote and gossip fodder, with a name that sounded like a belabored Rob Schneider punchline. It was dorky, crass, oddly designed, unsophisticated, unspecific, and it never could have worked without these aspects commingling.

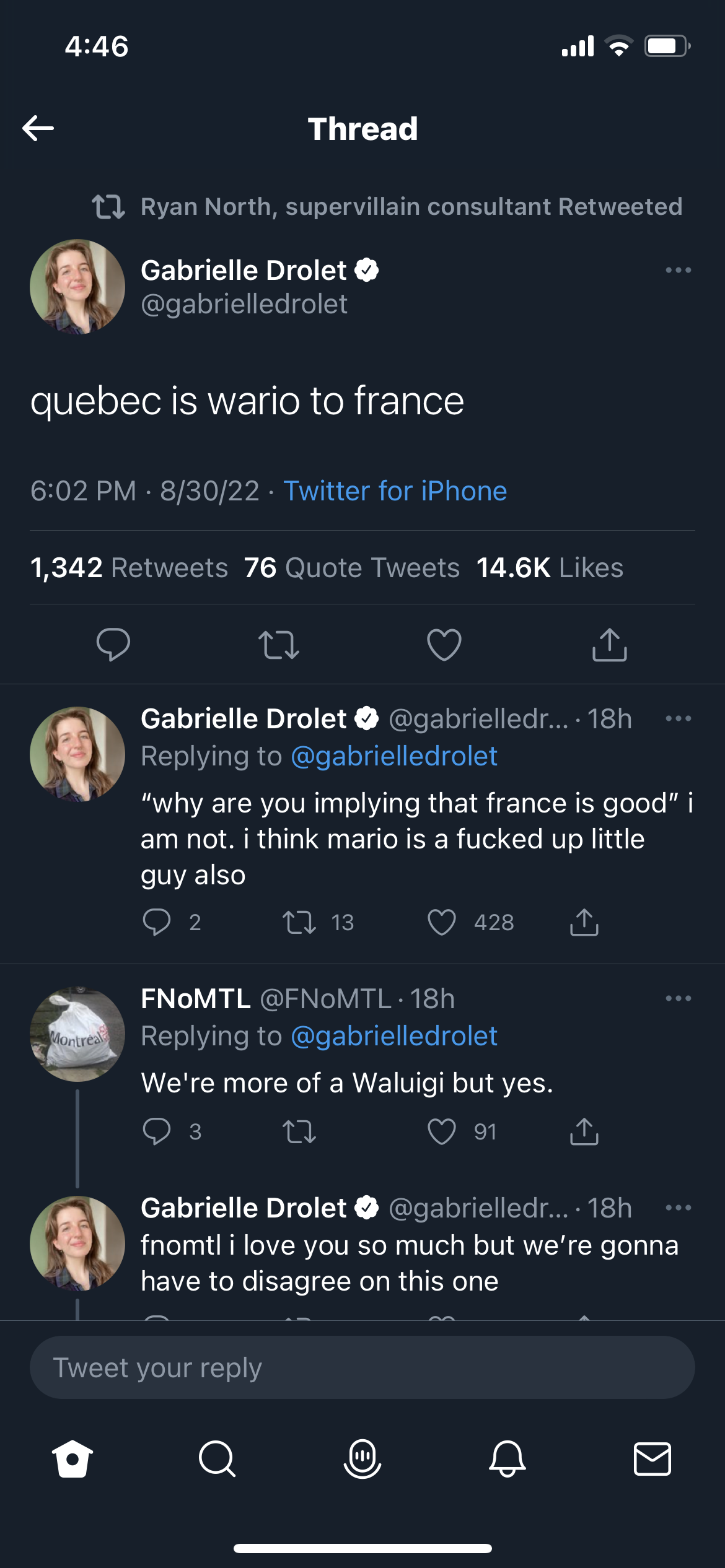

It is also nice to finally have reached critical mass in my pop cultural interests—the references in my scholarly texts are things that I no longer require a footnote to understand. What I’m saying is that Lurking feels like it was written for me. Example: “I often think about Amazon as the ultimate Wario to the public library. Like a library, it began with books, and later expanded operations to include Hollywood studio productions, cloud infrastructures, groceries, and space missions. A library is also more than books.” Any book that trusts its readers enough to just know what a “wario” of something is simply earns my love and affection.

This was a treat to read, which honestly surprised to me; the cover and the title/subtitle are grey noise, simply there. I expected another technical treatise on corporate domination. How a Person Became a User did not exactly thrill me, pull me in, or prepare me for an authorial tone that I wanted to hang out with: “Myspace was transparently scuzzy and unabashedly vulgar, but that was preferable to covert slime.” Yes, agreed! I was a hanger-on to myspace well after the network effect should have yanked me into facebook, and the author gets it.

What I came away with from Lurking wasn’t new hot facts about the tech industry, but insightful interpretation, a socially cohesive overview, and a splash of nostalgic warmth. If you didn’t live through this era, there are likely fascinating and improbable-seeming facts that would leap off the page and embed themselves into a book review. Most of the (many, many) passages I tagged were because the writing was clever (“Later, the internet transitioned away from anonymity toward online environments that demand authenticity, even if there are just as many lies.”) or the joke landed (“I guess all that outweighs how much I wish I could have been there to comment on The Prisoner and see my username on the Sci-Fi channel at that ungodly hour.”). It was not always the content itself, but it was always the delivery, which was impeccable.

In a certain sense, the voice of this book has become monolith. The flowerprint & chambray Brooklynite has triumphed in the “musing about the internet” genre (see also Everything I Need I Get From You, which I read directly after this and may have directly—unfairly?—informed this opinion). I absolutely will not stop reading interwoven cross-cultural syntheses of the web1.0 era, and if it’s always Jenny Odell and Astra Taylor blurbing the back cover, more the better.

Read this book if you want to resubmerge into a period of the internet that burned brightly but too short. It was an interregnum, a period so short that anyone who was “there” should count themselves lucky. Year 2000 broadband? That was my Woodstock, man.

This should be the end of the review, but I have one more thought about the internet. It’s still a really weird place on the fringes, even after the “…concentration of power, which Amazon, Google, and Facebook have shored up…”, which did seem unlikely back then. There’s always a chance to stumble across someone making specific value claims about vague thoughts that nearly have meaning: sandwiches cut at a diagonal having more valor than the vertical slice, for example. These really grandiose claims about particular mundanity are funny.

Lurking has me out here thinking about the rounds I would make, the pilgrimages online to all the websites I liked, just to check if they had updated. Personal websites like Line on Sierra remind you that casual content creators sometimes just stop: unlike the TikTok or Instagram algorithms, no overarching force is rushing into forcefeed you content in their absence. The web was connected, sure, but the navigation was absolutely terrible. And we liked it that way.

To end on an extended metaphor, if you know (or are) an American who used to drive for vacation in the time between cars & hotels being normalized but interstate highways not being ubiquitous, that was the internet before web2.0. Roadside attractions and beautiful sights competed for attention, and you’d stumble across local cuisine, listen to regional radio stations, and even just passing through would see more of a place than an overnight in the little highway offshoot food/hotel stripmall affords now. For my East Coasters, think US Highway 1 vs Interstate 95. Sure, you can get where you’re going faster on 95. But it’s going to be monotonous & grey the whole time. That’s facebook. Instagram. Even TikTok. Is there a chance our hacky use of the bad metaphor “The Information Superhighway” informed what the internet eventually became when the kids who grew up hearing it over and over started creating things?

Nah, probably not. Or else we’d have sick keyboard skateboards by now.

Go read Lurking!